It’s time to get real about TCO.

Here in Cincinnati, we’re about to get a streetcar. Exciting, right? Never mind the fact that we used to have them decades ago, but got rid of them because buses were cheaper and streetcars were confined to tracks, among other reasons.

Before it was approved, one of the interesting debates about the streetcar was the cost. There were a lot of people suggesting that the streetcar could be profitable, or at least cost-neutral. The operating budget for it was forecast to be roughly $3 million per year. But, that doesn’t account for the $100 million plus in construction costs. If you amortized that over 30 years, the principal and interest would alone be over a million dollars a month! Pretzel math at its finest.

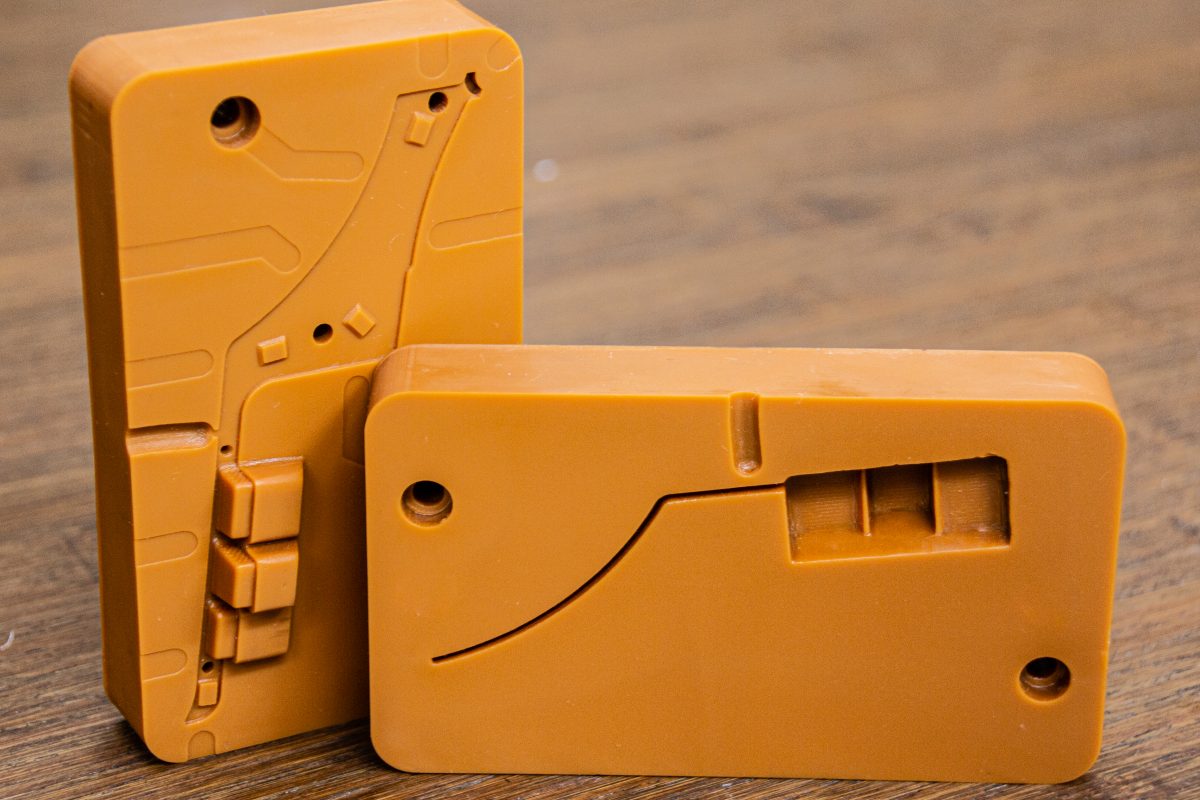

I see a lot of the same things happening in 3D printing. The term “total cost of ownership” is used very loosely. Sometimes a manufacturer (or members of the press, or others) will only account for the capital cost. Other times they’ll include the cost of maintenance and consumables. Occasionally they’ll even take a stab at the labor cost. But almost inevitably they’ll omit a lot of other things.

If you’re trying to justify a piece of equipment internally, or worse yet buying it so you can resell the output, not having a thorough understanding of total cost of ownership (TCO) can have dire consequences.

Let’s look at some of the factors that make up TCO.

Purchase vs. Lease vs. Rental

Here’s a fun fact. Did you know that when Xerox launched the first copier (the 914) they originally planned to sell it, but because the price was so astronomical (for the time) they ended up financing the capital cost to build them and instead of selling them, placed them as “rentals”?

Here’s more from a Forbes article:

“The painstakingly developed product had an initial sticker price of $29,500—an enormous sum for a piece of office equipment. Realizing that such a price would prohibit mass sales, Haloid-Xerox adopted the strategy that made the product successful. It would lease the machines rather than sell them. Xerox set a monthly rental rate of $95, which included 2,000 free copies. Clients would then pay four cents for each copy beyond the initial 2,000, which were tabulated on meters installed on every machine. Wilson described the leasing tactic as ‘the most important decision we ever made—except for backing xerography itself’.”

To be clear, it seems even Forbes doesn’t understand the difference between a lease and a rental. There are differences.

From an accounting perspective, a purchase is almost always a capital expense. Sometimes a lease can qualify as an operating expense, but in other cases, where the buyout is fixed, it must still be booked as capital. Rentals can more often be claimed as an operating expense.

Here’s why that matters. Companies can typically receive more benefit faster from an operating expense than they can from depreciating a capital expense.

Over time, Xerox moved away from the rental program, to selling more machines outright, and then eventually to more traditional leasing, which they did in-house until 2001, when that was outsourced to GE Capital.

But around the same time, customers with huge fleets of machines started questioning the value of leasing. On most high-dollar equipment sales, the lease term was typically 5-7 years. But, Xerox would announce a new, better, faster machine every 2-4 years. So, they upgraded and rolled the remaining cost into the new lease. After a while it became unsustainable. If you’re really interested, you can read more about the problems that caused here.

So, the smart ones started putting pressure on Xerox and others to move to a revenue sharing model which, believe it or not, was based on machine rentals.

Now you see companies like Carbon offering their new M1 printer on a subscription program. Everything old is new again. But I digress.

Fixed Vs. Variable

Regardless whether it’s amortization, a lease payment a rental or anything else, the investment must be accounted for in TCO. It usually ends up being expressed as a fixed monthly fee.

Which brings up the concept of fixed vs. variable expenses. Fixed are those things you pay for whether or not you run your machine. Variable costs theoretically only occur when you push the big green button and start printing.

Machine Service and Warranty

Some companies include a service base or minimum monthly amount that is charged for having a technician available to fix the machine. Others charge for service based on usage. Still others charge for parts that are not considered “consumables.”

Consider the MakerBot Smart Extruder for a moment. Like any other extruder in an FDM printer, it was responsible for heating plastic filament and applying it in layers on the print bed. But unlike “dumb” extruders, it was also responsible for automatically leveling the build plate and sensing print failures.

But it turns out MakerBot’s extruders weren’t so smart after all. They became known for quickly failing. In some cases, customers were only getting 40 to 80 hours of production from them. At roughly $165 per extruder, the replacement cost was significant. They were not covered under warranty and since they were not considered a “consumable” by MakerBot, the impact on cost wasn’t clearly understood by consumers. The response was predictably negative and once it reached critical mass, a class action lawsuit was filed.

Scenarios like this happen more often than people think. It pays to understand the underlying technology when purchasing equipment. You must know what is covered under a service agreement or warranty, and what is not. Those things that aren’t should be accounted for.

You also have to decide how you’ll manage replacement parts. Even though you might think of an extruder for example, as a variable cost, would you wait until it breaks to order a new one? Not if you value uptime.

Consumables

In theory the cost of consumables is pretty straightforward. But what about waste and other material loss? If you have to pitch a vat of resin as part of a preventive maintenance cycle, or trash a print that geeked out halfway through the run, the cost of those wasted materials can be significant.

Even in the successful production of parts, there can be significant waste. Consider selective laser sintering (SLS) for example. With SLS, parts are made in a bed of powder. Once the parts are made they get pulled. Any remaining material is scrap.

Even in the successful production of parts, there can be significant waste. Consider selective laser sintering (SLS) for example. With SLS, parts are made in a bed of powder. Once the parts are made they get pulled. Any remaining material is scrap.

Both intentional and unintentional waste must be factored into any understanding of TCO.

Labor

This one gets really tricky because so many people only consider the variable expense of labor. Say you pay a machine operator $30 an hour. It’s very easy to divide that number by an hour’s worth of productivity and call it a day. But that’s not how it really works, is it? You pay that operator full time, whether the machine is running or not. You also pay for all of their benefits, taxes, training and other expenses.

Now you might say, “that’s not fair. I have several machines and my team members operate many simultaneously.” OK, then total up your expense on all operators and allocate that expense by machine.

You might also say, “that’s not fair either. My employees multi-task, doing more than just operating 3D printers.” Then figure out what else they do and allocate their time to each task. But, you’re fooling yourself if you think their (or your) time spent running a machine is free.

Productivity

While we’re on the subject of labor, it’s probably a good time to talk about productivity. You don’t get 60 minutes of an operator’s time. They eat lunch, take breaks, goof off and do all kinds of other stuff that doesn’t make you money.

Here’s a way to tackle that. Assume your machines can produce 20 cubic inches of material in an hour at 100% productivity. Instead factor them at a maximum of 70% productivity. You’ll account for operator productivity and better account for some of your other unscheduled downtime.

While we’re thinking about productivity, let’s discuss capacity. If a machine can do 20 cubic inches an hour, you might be tempted to think it can do 480 ci a day and 14,400 ci per month. There are so many reasons why that won’t happen that I won’t even bother boring you by listing them all out.

Here’s a nugget for you. When thinking about the cost of productivity, look at it this way. Your first shift should cover your expenses. Your second shift should make you some money, and your third shift is the cash machine.

Remember above when I said factor them at 70% productivity? Your goal is to run your equipment at 70% for three shifts. Once you‘re doing that, go buy more. Not before, unless your business advantage is based on speed. But also remember that speed costs money.

In most manufacturing environments, work is priced on speed, quality and cost. You can typically provide two but rarely all three at once. Want low cost and high quality? You’ll have to wait. Want high speed and quality? You’ll pay for it. Want quick turn and low cost? Quality will likely suffer.

Overhead

That’s only the tip of the iceberg. There are plenty of other costs hidden in these waters.

Say you’re a $5 million (revenue) 3D printing service bureau with 30 employees. Many of them are overhead, including management, marketing, accounting, human resources and more. You can’t bill for their time directly, but still they get a paycheck.

There are several ways to handle overhead. The easiest thing to do is ignore it, but that’s a going out of business strategy. Perhaps the best way is to establish cost centers for every product and service, and then allocate a share of the burden to each.

Let’s continue with our example of the $5 million shop. Say you have $1 million a year in overhead. You set up cost centers for prep (software, file fixes, slicing, etc.), production, and post-processing. If prep accounts for 20% of your revenue, you could allocate it 20% of the burden. If production is 60%, it gets that share of burden and post-processing, which accounts for 20%, gets the remainder.

You could break it down further. Say within your production environment you have 6 different machines, each accounting for an equal share of your revenue. You could allocate each with 10% of your burden or in the case of our example, roughly $100,000 per year in fixed cost.

Facilities

If you’re running a $5 million shop, chances are you’ve got a decent size facility. For grins, say it’s 30,000 square feet. When buying a new machine, it’s tempting to say, “it takes up 20 sq ft, so that’s what I’ll allocate.” Reread the section on overhead. It applies to your building as well. It’s best to allocate your square footage by cost center. That way everything that’s revenue producing takes a chunk.

Also, don’t forget that there are many other costs in your facility. Utilities like heat and air are big ones. In a service bureau environment you might need to tightly control the temperature, humidity and ventilation. Electric is another big one. Some small shops in certain industries draw more power than much bigger buildings in others. Hell, even your phone lines, internet and security system cost money. They have to be allocated. Oh, and don’t forget janitorial, landscaping and snow removal. Those guys aren’t free.

Administrative Costs

It doesn’t end there. You’ve got to pay for lawyers, accountants, and insurance premiums. Have a board meeting once a year where you and the family travel to Florida? That’s more burden that has to be allocated. Nobody said running a business was cheap.

Opportunity Cost

If you weren’t spending money on a new machine, how else might you invest it? If you’re storing your classic car in your warehouse instead of billable inventory, what’s that worth? It’s much harder to allocate opportunity cost, but you’ve got to be aware of it.

Others

Again, there are many other costs that I haven’t addressed in this article. Let’s take marketing for example. Some might look at it as a profit center, but it still has cost. In fact the average B2B company spends 2-10% of its revenue on marketing. So, if you’re a $5 million shop you should be spending at least $100K a year on marketing.

Selling expenses are another. When I worked in sales, my expense reports were typically among the highest. Why? Takes money to make money, bub. Dinners, drinks, golf and other client entertainment all drive the top line, but also ding the bottom line.

Articulating Cost

Once you have a thorough understanding of your costs, you have to decide how you’ll articulate them. Prep typically includes the fixed costs of job setup and management, but might also include an hourly rate for repairs, slicing and other work. Production can also have a make-ready cost, or could simply be based on a cost per cubic inch (or centimeter for those who are metrically inclined). If post-processing is manual, it might be based on the time and materials involved. If machines are required for finishing, they might have their own make-ready and run costs.

Maybe what you come up with looks something like this:

While that alone can be difficult to estimate one job at a time, it gets even harder in a situation where an internal or external customer has significant volume and wants to establish some form of contract pricing. You can either try to come up with a formula that accounts for your many fixed and variable costs, or you can average them together and provide a simple cost per cubic inch.

But keep in mind that if you’re averaging, it will be based on a set of assumptions. If those assumptions aren’t met, you will lose money. If they’re exceeded you’ll be more profitable, but also more susceptible to competition. If you’re in the goldilocks zone, everything will be just right.

A Partnership in Profitability

I could go on and on. But maybe at this point you’re asking how a 3D printer manufacturer, or for that matter someone in the media could be expected to understand and factor all of that into their assessment of total cost of ownership. They can’t…independently. It takes collaboration between two parties to assess real cost.

Equipment manufacturers have to provide you with a set of assumptions. What is the capacity of their machine? What is the consumable cost per cubic inch? How much machine down time can you reasonably expect? Etc, etc, etc. You have to make your own assumptions about the rest.

But an equipment provider worth their salt should be able to help. Especially if you are printing for pay, but even if you are justifying a machine for internal purposes. They should provide you with tools that help you identify and allocate cost. Like it or not, you’re in business together. Your success is their success.

On the off chance they can’t or won’t help, call someone like me. Yes, consultants are costs too, but if you get a realistic picture of total cost of ownership out of it, it might just be worth the investment. Maybe we’ll even get dinner or go play a round of golf. Just don’t forget to allocate it!