3D printing’s early success came with prototyping, but that market is finite. The real money is in production. In most cases it’s still more expensive than mass manufacturing. Eventually it will be more competitive, but even now, it offers a speed-to-market advantage that mass production can’t match. That’s a BIG opportunity.

Say you’re a product designer. You woke up the morning after Trump’s UN speech and thought, “I’m going to design a Rocket Man butt plug.” Don’t laugh. There are already Donald Trump, Kanye West and Tom Brady butt plugs, among many others.

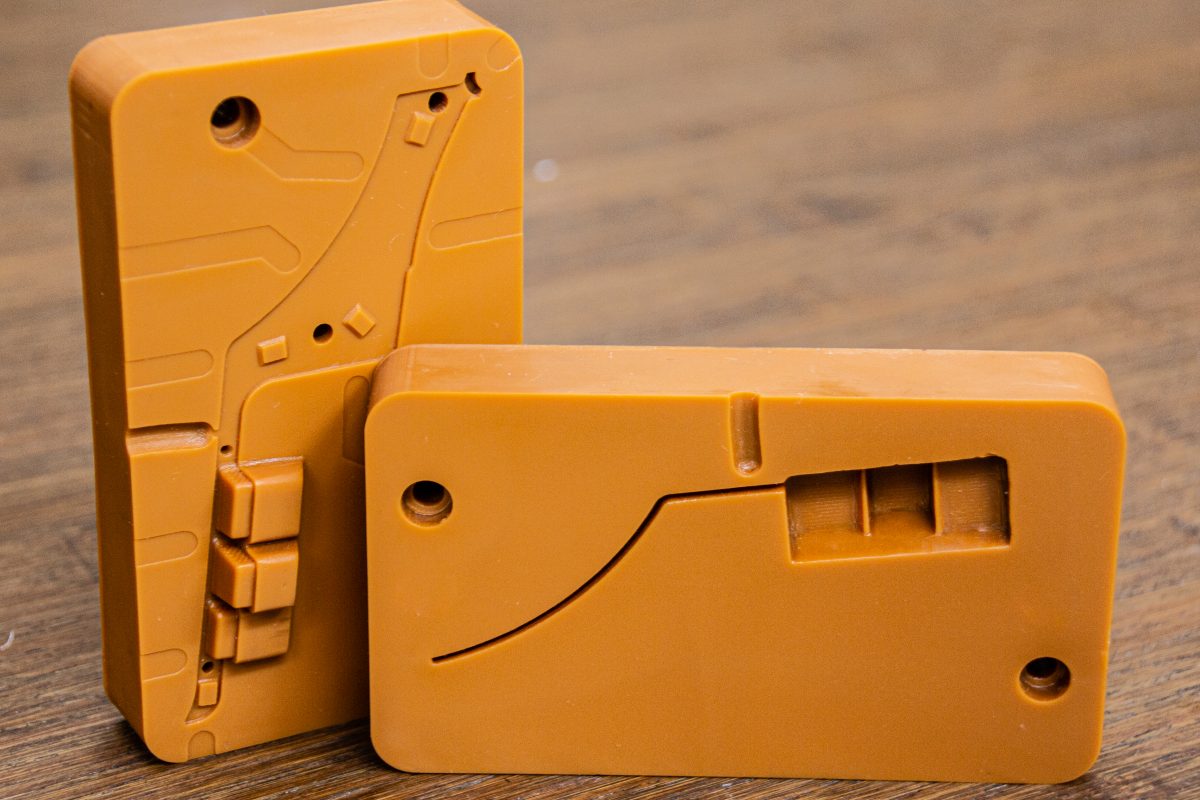

If you were going to mass produce such a product, you’d go through several design iterations and probably use 3D printing to prototype it. Then you’d send your design to China to have it injection molded. Six weeks later you’d have 10,000 or more Rocket Man butt plugs. You’d probably list them on eBay, Etsy and other marketplaces and hope there’s still enough demand.

If your product sold well enough, you’d make a tidy profit. If it didn’t you’d lose your ass.

With 3D printing, you could go through the same design process, list your product and produce them in small batches, or even “on demand.” The cost of the product would be much higher, but you’d have significantly less risk and you’d get your product to market six weeks faster.

The printing and apparel industries have used this strategy for some time. Right now, you can go online and buy a Rocket Man t-shirt.

The printing and apparel industries have used this strategy for some time. Right now, you can go online and buy a Rocket Man t-shirt.

In some cases, products like these are screen printed (a form of mass manufacturing). In others they are digitally printed. Companies make those decisions based on demand. But there’s a big difference. With screen printing you can turn a job in one day. Injection molding, vacuum forming, machining and other forms of mass manufacturing typically take far longer.

Some might argue the economics. You might say, “I can produce that Rocket Man butt plug in China for pennies.” You could also print that Rocket Man t-shirt in China for under $5. Producing it on demand might cost $15 or more. Who cares? The company is selling it for $24.95!

The bigger challenge with the lowest cost argument is that in order to get that very low price, you need to manufacture at a very high volume. With t-shirts it gets even more difficult. You have to decide on an assortment of colors and sizes. Inevitably, you’ll end up with too many in pink or too few in size XXL.

Maybe that’s not a problem with butt plugs. I’m not an expert on the topic so I don’t really know. But, what I do know is that if you choose to mass produce, you’ll have to forecast demand. The math works really well at higher volumes. Say you bought them for $.50 each and planned to sell them for $5. If you sell 10,000, you’ll wish you made more. Even if you only sell 1,000, you’ll still break even. But, if you end up selling 100, you’re screwed.

Marketing In The Moment

Recently I read a linkedIn post by Tom Goodwin. If you recall, he’s the guy who famously noted that “the world’s largest taxi firm, Uber, owns no cars. The world’s most popular media company, Facebook, creates no content. The world’s most valuable retailer, Alibaba, carries no stock. And the world’s largest accommodation provider, Airbnb, owns no property.”

Anyway in this new post he said:

“If there was one single thing that you could claim to be most indirectly and directly responsible for modern woes, it would be the inability of media to make money in any way accept from attention. From fake news to clickbait, extreme opinions being normalized, to a refusal to cover the complex or apply nuance, a lot of what’s wrong is because media is forced into cheap, fast news.”

He’s right. But what struck me again is how much of an opportunity that creates for product designers to “market in the moment.” Every day it seems, a new trend creates new opportunities for products.

A quick scan of trending topics brought me to this series of Disney illustrations, reimagined for 2017. Nearly every one could spawn a product. From a Pinocchio selfie stick to a smartphone case featuring young Arthur so engrossed he can’t be bothered with Excalibur.

Licensing

It’s not the first time I’ve written about marketing in the moment. During a Super Bowl halftime show a few years ago, singer Katy Perry was flanked by two dancing sharks. One looked a bit off, and “left shark” quickly became a trending topic.

A designer created a figurine of left shark and began selling it on online. Katy Perry’s legal team found out and sent him a cease-and-desist letter.

In my mind it would have made more sense for them to embrace the phenomenon and to benefit from it financially through licensing.

I even suggested a formula for success:

Talented Designers + Passionate Fans + Digital Technology = Huge Opportunity

Certainly the combination of licensing and crowdsourcing comes with equal parts good, bad, and ugly, but it’s not that hard to differentiate. More importantly, providing a sanctioned way to leverage branded content gives designers access and a financial incentive, while also helping brands protect their properties.

Speed-To-Market

Here’s the reality. Digital technology creates a speed-to-market advantage. As I noted in my article about left shark:

“3D printing allows people to create physical products from digital files. Because it’s digital, it removes many of the barriers typically associated with making and selling things. No big, upfront investment in manufacturing means nearly anyone can turn their idea into something real. No long lead times, means they can operate in the moment. Further, online marketplaces make it possible to list and sell nearly anything, quickly and with little effort.”

In many cases, speed-to-market is more important than cost competitiveness. The other guy might be cheaper, but it takes him far longer to get his product to market. If there’s an audience – whether we’re talking about Rocket Man butt plugs, left shark figurines, or the myriad of mundane, everyday products, speed wins. And often, it’s more important than the lowest possible price.

3D printing enables speed-to-market and that’s an instrumental benefit in the industry’s quest to move beyond prototyping into the real money of production.