A few years ago, 3D printing service bureaus seemed like a dying breed. Some were acquired by their corporate clients and others by their suppliers. But today things are looking up, and the future looks even brighter…especially if 2D printing companies enter the race.

The Acquisition Firestorm

In 2012, GE acquired Morris Technologies. Around the time of the acquisition, Randy Kappesser, composites technology leader with GE Aviation said that Morris (and sister company, RQM) would “be fully dedicated to GE Aviation and other GE businesses. The companies will meet their obligations to their non-GE customers. After they are met, Morris and RQM will be fully focused on GE work.”

Morris was one of the U.S’s largest players in metal additive manufacturing. Poof. Off the board.

Merge Or Compete

Also around that time, 3D Systems and Stratasys, two of the biggest suppliers of 3D printing equipment, were also on an acquisition spree.

Between 2000 and 2015, 3D Systems made over 50 acquisitions. Several of them were service bureaus. In 2011, 3D Systems acquired Quickparts. They also bought Formero and Kemo, and in 2012, Innovative Modelmakers, creating the basis of what was originally called Benelux.

In the U.S., 3D Systems acquired Laser Reproductions, an Ohio-based 3D printing service bureau that catered to industrial design firms and OEMs. They also bought American Precision Prototyping. In the press release for that transaction, 3D Systems noted that APP (and sister company APM) were “expert providers of rapid prototyping and advanced manufacturing, product development and engineering services” and that the purchase further extended 3D Systems “service bureau operations in the United States.”

All of these (and more) eventually became part of 3D Systems Quickparts division. In a 2015 SEC filing, 3D Systems described Quickparts as follows:

“We provide on-demand custom parts manufacturing via our Quickparts® brand through a global network of facilities. We provide a broad range of production and finishing capabilities…In addition to the sales of parts, we and our sales partners utilize our on-demand parts operation as a sales and lead generation tool, and third party preferred service providers can also use our on-demand parts service as their comprehensive order-fulfillment center.”

Stratasys was also busy on the acquisition trail. In 2014, it announced the purchase of Solid Concepts and Harvest Technologies. They were two of the U.S’s largest 3D printing service bureaus.

Solid Concepts offered significant capacity and infrastructure with six U.S. facilities that were staffed by approximately 450 employees. They maintained a broad mix of technology for additive manufacturing and served a diverse customer base across a wide range of verticals, including medical, aerospace, and industrial, among others.

Harvest Technologies had over 80 employees, was the first additive manufacturing company in North America to become AS9100/ISO 9001 certified, and produced end-use parts for multiple industries.

In the announcement Stratasys noted that with the acquisitions, they were “creating a leading strategic platform focused on meeting customers’ additive manufacturing needs through an expanded technology and business offering.” They added that, “the combination of Solid Concepts’ deep knowledge of manufacturing and vertical focus, such as medical and aerospace, and Harvest Technologies’ experience in parts production, as well as materials and systems knowhow, together with RedEye, strengthens Stratasys’ direct digital manufacturing and parts production expertise.”

After the sale they were combined to form Stratasys Direct Manufacturing.

The challenge of course, is that both 3D Systems and Stratasys also sell equipment. With all of that consolidation and the threat of supplier competition, people were reluctant to open new service bureaus and the independent service bureaus that remained were less willing to buy their new machines.

The other problem for both of those companies is that they invested a lot of money to acquire all those assets. Most of the deals were undisclosed, but Solid Concepts alone could have cost Stratasys up to $295 million.

That’s a lot of debt, and debt equals overhead.

You could argue that Stratasys and 3D Systems can offset some of that by using their own equipment and materials (at cost). But that only gets them so far, and in most of those acquisitions they gobbled up a bunch of competitive gear. That puts them in an even worse position than most first movers. They have to deal with debt and switching cost.

New Players Mean New Opportunities

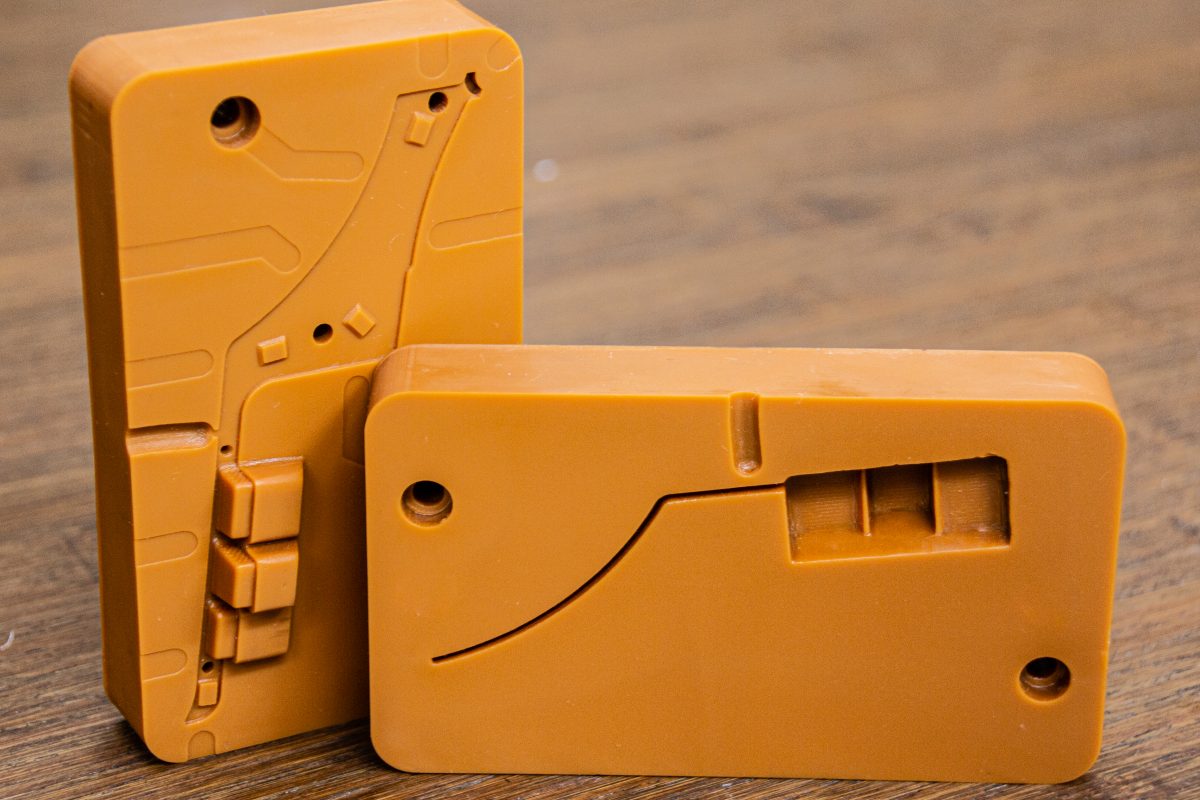

Image: Forecast 3D

Since then, several new 3D printing equipment companies have entered the fray. Carbon, HP and Desktop Metal all have fresh machines in the market. They each have a unique niche and none of them plan to compete with their customers.

Desktop Metal and HP have gone the more familiar route of selling and financing their equipment. While in the grand scheme of things, they’re less expensive than previous technologies, and for some applications FAR MORE productive, they still must be depreciated.

On a deal over $100K, that’s typically a five to seven year play. Will the technology still be viable that far out? Probably not, but for someone just starting up, that still punts the switching cost of upgrading at least three years down the road.

Carbon has taken a different approach. They’re renting their gear. That can lead to some tax advantages in the short term (operating cost vs. capital expense), and it can also reduce switching cost later on (assuming you keep the equipment the entire rental term).

In either case, it’s a big opportunity for startups to jump in and be more price competitive.

Now, some will complain a bunch of new players competing on price will result in margin erosion. They’re right, and the only way anyone can combat it is by selling on value instead of price.

Enter the 2D Printing Industry

None of this is new news. It already happened in the 2D printing industry. Over the last 30 years, suppliers competed, technology got better, early adopters got pummeled by switching costs, margins got whittled down, and lots of inefficient companies with poor value propositions failed.

But, the strong survived! They made smart investments, optimized their workflow, and differentiated their businesses.

They became masters. Their sales forces learned to sell consultatively, their marketing teams learned to use the web and eCommerce, their production teams learned that technology is more efficient than labor, and maybe most importantly, they learned to play well with others.

I’ve been evangelizing 3D printing to 2D printing companies since 2012. Even back then the writing was on the wall. Books, magazines, newspapers, and direct mail were all stagnant or on the decline. It’s gotten worse.

These companies are starting to open their eyes to new opportunities. They’re going beyond the forest and trees, taking an even bigger picture view.

While many in 3D printing are still debating the term (it’s not printing, it’s additive manufacturing!) 2D printers are starting to recognize the similarities.

In fact, 3D printing companies like MASSIVit are starting to tap into the trend. They’re targeting their machines at signage and display companies, providers of retail decor, and trade show and exhibit companies – all of which are key target markets for 2D printing equipment.

In an article I wrote for TechCrunch back in 2012, I made the case that 2D and 3D are a lot alike because the workflow is essentially the same. A file gets created, it gets sent to a machine, something gets produced, it gets finished and it gets shipped.

Certainly there are plenty of differences, some big and others small. But they’re not obstacles traditional 2D printing companies can’t overcome. They were going digital way before it was cool. They realize they’ll need new people, new processes, and new technology. But, they’ve been there and done that many times already.

Perhaps most importantly, they have access to capital. There are a lot of $10 to $50+ million printing companies out there. They have a lot of equity and great relationships with their lenders. If they wanted to invest a million or more in 3D printing tomorrow, the deal would be done by close of business.

So the question is…when will they?