A lot of progress has been made in 3D printing over the last five years. But much of that has been focused on the “what.” What printing technology? What materials? As the industry grows and 3D printing networks form, new questions must be asked.

Beyond The “What”

Many in 3D printing are so focused on the features, advantages and benefits of their machine, that they forget the “why” – another important question.

If you’re in sales or marketing you may have heard about a quote attributed to Harvard marketing professor Theodore Levitt. It’s said that he was approached by a tool manufacturer that was introducing a new drill. After they explained all of the great whiz-bang features about their product, Levitt noted that, “people don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill, they want a quarter-inch hole.”

Arguably they don’t even want a hole. They just want to mount a license plate bracket to the front of their car.

Converting from analog to digital also requires one to answer many “how” questions about each specific application. How will the input be created? How will it be submitted? How will the output be produced? How will it be inspected? How will it be delivered? How will it be priced?

As we continue to peel back the onion, other questions like when, where, and who must also be addressed.

The “Where”

A few years ago it seemed the prevailing thought was that soon, everyone would have a 3D printer sitting on their desk, workbench and kitchen counter. So far, that has not proven to be the case. In part, desktop 3D printers didn’t resonate with mainstream consumers because they were expensive, slow, and unreliable.

But it’s also because no one identified a killer application. When you’d ask why people would buy a 3D printer for their home, the standard refrain was typically something platitudinal like, “because you can make anything” or “it will democratize manufacturing!”

If you sent out a survey, asking the average middle class worker if they could afford to spend $500 on a new appliance, most would say no. Yet, many of them would respond via a smartphone that costs $600 or more. For most people those devices are no longer a luxury, they’re a necessity. Consumers need justification.

Crowdsourcing?

One way to do that is by helping them monetize their purchase. Networks like 3D Hubs offer some promise. Nearly 7,000 “services” have joined their network. A service can be an individual with one desktop 3D printer, or a full-on commercial service bureau with dozens of devices or more. Together, they’ve 3D printed over 750,000 parts.

But here’s one problem. Many of the people who join 3D Hubs get some orders, but not enough to get full ROI from their investment in 3D printing.

The other big problem with a crowdsourced approach is that there’s no built-in way to manage quality and consistency from order to order and from location to location.

Centralized Production

A better solution is for someone to own it. All of it. The entire workflow…and there are basically three ways to do that.

The first option is to centralize production. Put all of the people, processes, and technology in a limited number of facilities. Optimize everything and tightly control what is delivered to the customer.

Vistaprint is a good example in 2D printing. They’ve built a web-enabled network that provides consistent, high-quality printing to millions of customers. Production is centralized in a few tightly managed facilities. Shapeways, Sculpteo and other service bureaus are taking a similar approach to 3D printing.

Decentralized Production

Another option is to decentralize production. In the 2D world, think photo labs. Kodak has over 100,000 kiosks scattered around the globe. You can walk up to any one, insert a thumb drive and print a photo.

In the 3D world, several companies have experimented with similar types of machines. Piecemaker, for example, focuses on toys and their solution allows customers to select from a catalog of 3D printable products, personalize them and print them onsite.

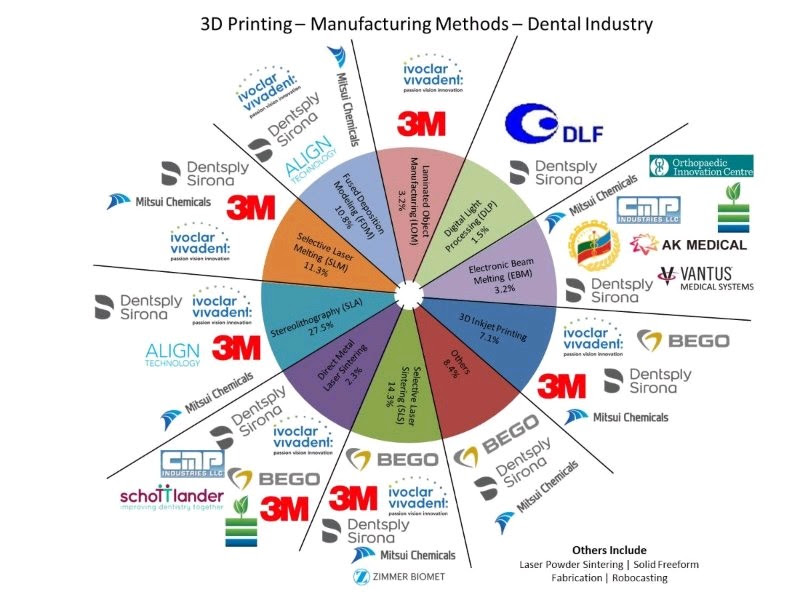

You also see decentralization in professional environments. The dental industry was an early adopter of 3D printing. Dentists bought 3D printers and began using them to fashion drill guides, mouthguards, and other tools that were useful for their practices.

But, what about quality?

For good reason, the medical device market is tightly regulated. According to rules determined by government bodies such as the US FDA, mass-produced devices must be tested and approved. They also have to be produced, packaged, stored and shipped appropriately.

However, devices made by “licensed practitioners, including physicians, dentists and optometrists, who manufacture or otherwise alter devices solely for use in their practice,” are exempted from many of these types of regulations.

On the plus side, this allows doctors and dentists to innovate more quickly. On the downside, it circumvents rules that are in place to ensure patient safety.

AdvaMed (the industry association for medical device manufacturers) wants the FDA to rethink the exemption, specifically because of 3D printing. They think that point-of-care establishments should be subject to FDA requirements, “including premarket review if applicable, and post-market controls such as establishing and maintaining quality systems and adverse event reporting.”

Is this competitive lobbying, or do they have a point?

In a recent article, Al Siblani, the CEO of EnvisionTEC (a company which makes 3D printers for the dental market) wrote, “while we recognise medical device manufacturers want to protect patients, and also themselves from the threat of manufacturing directly at the point of clinical service…we do recognise that the market for 3D printers for clinicians has become a bit like the Wild West.” As a result, his company welcomes “direct regulation of 3D printers and materials.”

But again the focus is on the what – printers and materials. How, where, when, and who also have a big impact. In a decentralized environment, they’re all harder to standardize and control.

Hub and Spoke

A third approach to “where” combines the benefits of both. In a hub-and-spoke model each location has some capability and capacity, but the organization also offers regional production centers which can manage overflow, higher volumes, and unique applications. Typically the hubs use higher-end equipment, handle more materials and offer more complex finishing capabilities.

An example from the 2D printing world is Staples. Each store has a copy center where customers can place orders for printing. The stores can print small jobs like reports, presentations and such. Larger-volume jobs are sent to one of the company’s regional production centers. These also manage large-format projects like banners and print on unique materials including vinyls and plastics.

In the 3D world, UPS has taken an early lead in this direction. They now have smaller 3D printers in over 60 of their UPS Stores. They’re primarily servicing small businesses and walk-in customers.

They also have a partnership with Fast Radius, which operates a 3D printing center inside the UPS hub in Louisville, KY. This center can provide overflow for the stores, but also offers an online service similar to those offered by Shapeways and Sculpteo. The system is managed through a software partnership with SAP.

The Who

Building a distributed print network is an expensive proposition, regardless of how it’s constructed. You not only have a big investment in equipment, but also in processes, people and a bunch of other stuff. You can achieve a return, but even with a killer app, it’s a longer-term play.

But, the threat of disruption is also a real factor.

If You Can’t Beat ‘Em, Join ‘Em

Device manufacturers are obviously concerned enough that they’re lobbying for tighter regulation of 3D printing in the medical industry. Johnson & Johnson also voiced concern about 3D printer exemptions, but then, very recently announced that it was purchasing a group that makes 3D printed, bioabsorbable implants.

UPS also seems determined to be a player, even though their entry will eventually be seen as a threat by their core customers – those who manufacture and sell the mass-produced products we all use every day.

Plenty of others have jumped in. But what shocks me is retail. They’ve been disrupted ten ways to Sunday. eCommerce, mobile, and new business models have all taken their toll. So far this year over 2,600 U.S. retail locations have closed. If they continue at this pace, 2017 could eclipse 2008 (a major recession year) in total store closings.

3D printing could be a game-changer for them. But in the face of adversity, instead of taking the lead, many revert to their time-honored tradition of focusing on “core competency.”

Whatever.

Sooner than later, more distributed 3D print networks will form. They will massively disrupt their target markets by distributing the manufacturing of products as close as practical to the user. They’ll also open a flood of hardware innovation because product developers (of both human and artificial intelligence) will no longer be constrained by the economies of scale. Personalization will throw gas on the fire, allowing people to tailor products to meet their specific needs.

Infrastructure

Companies with a large distribution network have an advantage. They already own real estate. They can transition from analog to digital inventory while keeping many of their other services in place.

Consider car dealers for a moment.

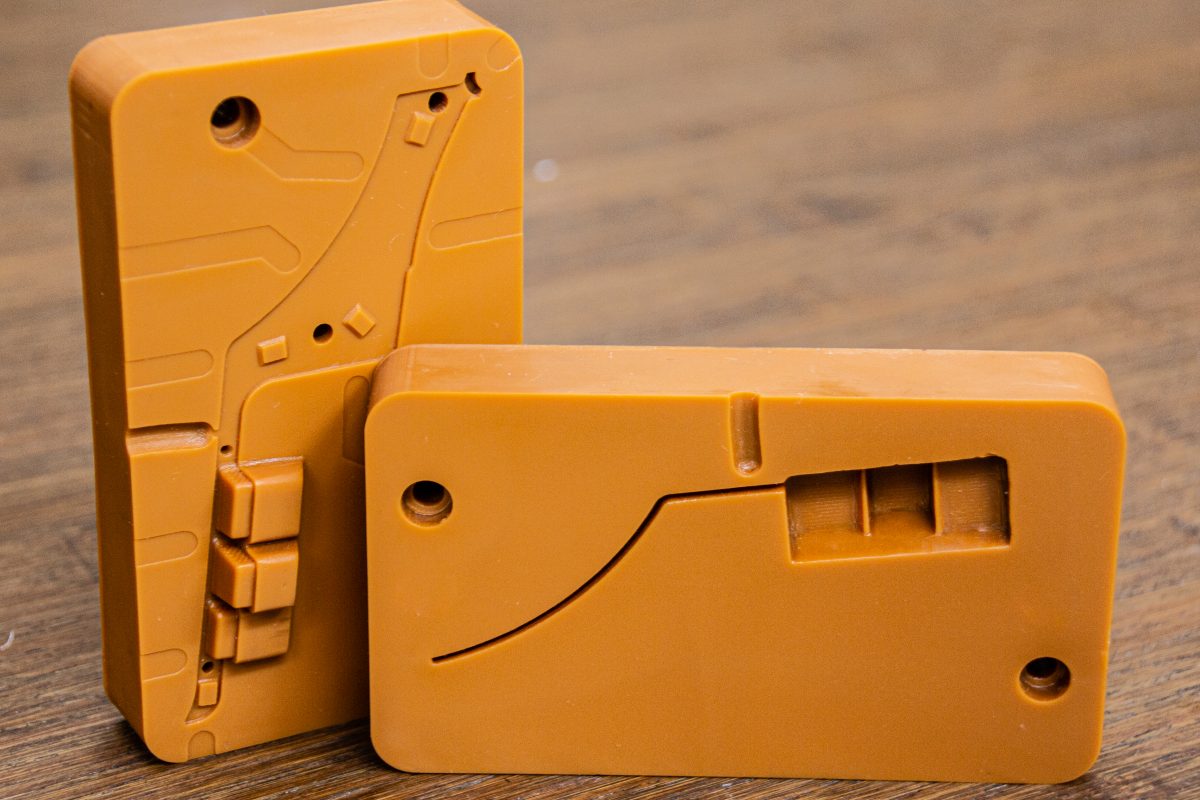

3D printing could allow a dealer to manufacture some things on demand, reducing their parts department’s inventory. It could also allow them to earn revenue on new products that they don’t carry today. They could even expand beyond their market segment, making parts for commercial trucks, motorcycles, RVs, boats and more. They could even expand into other retail categories.

They could be successful because their infrastructure is an asset.

You can find examples like this in almost every business sector. Large companies with lots of locations, inventory and customers, each servicing a specific market niche. Every single one of them ought to be exploring ways to reduce their costs and generate more revenue.

Supply chains are expensive. Digitizing them makes sense, even if it is a long-term play.