Have you heard about the labor dispute that’s been brewing in Long Beach and other U.S. ports? Apparently, some longshoreman aren’t happy making $147,000 per year…or that’s spin from the Pacific Maritime Association. According to The International Longshore and Warehouse Union, the average dock worker only makes $26 – $36 per hour and some percentage don’t work full time.

I’m not taking sides in the dispute. Shippers can only afford so much. Dock workers do a dangerous and difficult job. To resolve the problem, they’ll probably both make concessions and punt the ball down the field. But, that’s short-term and doesn’t solve the issue. This isn’t the first time these two parties have clashed and it won’t be the last.

For retailers and their stakeholders – customers, suppliers, employees, and investors, it’s relevant and all too real. Due to the dispute, gridlock at the 29 west coast ports has a significant amount of product sitting on ships that should be arriving at stores right about now.

Also in the news, a global retailer recently said it would dramatically reduce the number of products it carries. Tesco announced that it would cut the number of stock keeping units (SKUs) in its stores by 30%. They currently stock about 90,000 products, so somewhere north of 25,000 brands could soon be receiving a “Dear John” letter.

Apparently, too much choice is a bad thing. The average consumer only buys 400 products per year and only has about 40 products that regularly end up on their weekly shopping list. Tesco carries over 200 brands of air fresheners and 28 brands of ketchup. Their competition carries only a few, and as a result enjoys lower supply chain cost. Redundant inventory at hundreds or thousands of locations is just too expensive.

Maybe it also signals a change in consumer behavior? Do shoppers really care about brand names anymore? A brand used to signify quality, but according to a recent article by Itamar Simonson, a marketing professor at the Stanford University Graduate School of Business, consumers are now using other tools. According to Simonson, “People today can easily and quickly access a lot more information that they used to. That fundamentally changes how people make decisions…if you can access better information about a product’s quality, perhaps you’re less likely to rely on imprecise proxies like brand names, price, and where a product is made.”

While each of these recent articles discusses a different topic, I can’t help but feel as though the stories are all interconnected. Retailers are having trouble getting product to their stores and they’re questioning which products are relevant. They’re also faced with changing consumer behavior and that has some even rethinking the value of a brand.

In a piece I wrote a while back about how auto parts stores could leverage 3D printing, I devoted a considerable chunk to the supply chain. Back then, I made the argument that a company like Advance Auto Parts could save $17 million per year by converting just 140 of their products from mass production to digital manufacturing via 3D printing.

Today, I’d say the savings opportunity is much bigger. If they could convert 3% of their 500,000 SKUs, they’d potentially save $72 million per year in supply chain costs. And unlike Tesco’s slash-and-burn solution, those products would still be available to consumers.

3D Printing Bridges the Gap

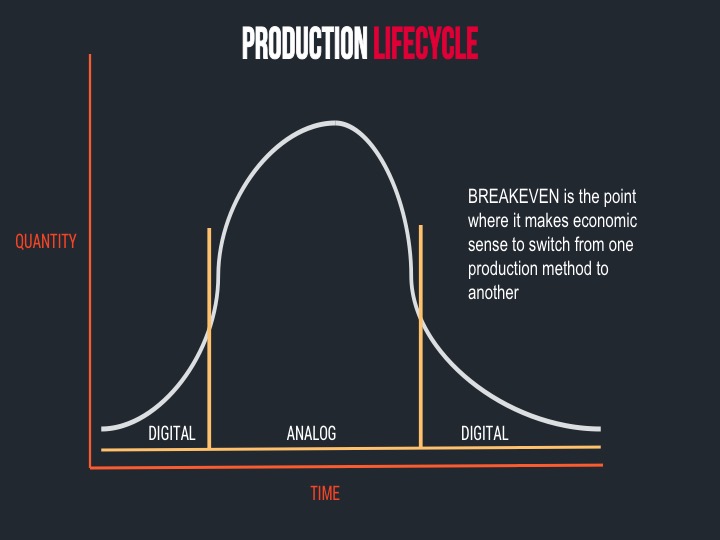

People frequently ask me if I think 3D printing will replace mass manufacturing. I say no, they’ll coexist. Think of the product lifecycle like a bell curve:

3D printing (or any digital manufacturing technology, for that matter) makes sense at the beginning and end, when demand is unknown. At the front end, when a brand or inventor is trying to get their product to market, there is significant cost. Digital mitigates the risk for both the retailer and supplier.

Then as demand builds, there is a middle opportunity to pre-print product, professionally package it, and allow it to compete on shelf. This gives the retailer and supplier real data they can use to make a decision about whether or not to stock the mass produced version, and where.

At the end of the lifecycle, when there is still some demand, but not enough to justify ongoing production, its back to digital.

For any given product, there is a clear “breakeven” between digital and mass. On a smartphone case that might be 500 units. On a tire stem cap, it might be 5,000. There are many variables that can have an impact.

If history is any kind of guide, the breakeven is likely to grow over time. As speed and quality improve and cost decreases, digital technologies can have an impact later in the curve.

Investment Now, Gratification Later

Consider this. The average company in retail probably spends 10% of revenue managing their supply chain. Even the best spend 4 or 5%. For a $50 billion retailer like Lowe’s, that’s somewhere between $2 – $5 billion annually.

If you applied Google’s 70/20/10 model, where 70% of resources are spent on core, 20% on things that are related to core, and 10% on blue sky projects, where would digital manufacturing fit? If 3D printing could impact 3% of your transactions in the near term, and 20% or more in the long term, what kind of investment would you make? I know it’s simple math, but 20% of $5 billion is a billion dollars in savings, annually!

Note that I am not suggesting retailers start by manufacturing 3D printed products in-store. First they have to become acquainted with the process and deeply consider the many implications. In my experience, the best way to do that is to go through the process of listing and selling products online. It can easily take months to accomplish this – there are a lot of hoops to jump through!

Time is Not a Friend

Here’s the problem though. In retail, it’s all about speed-to-market. It is very difficult to catch up. eCommerce and mobile are two examples. If you were delayed there, you had to pay significantly to catch up.

If you start tomorrow and it takes a year to “figure 3D printing out,” you’re already behind. Way behind. We launched our beta with Amazon nearly a year ago. Since then, we’ve helped Walmart, Rakuten, Sears and others begin their process.

The problem is compounded. The pace of innovation is so fast today, that even a year behind might be too much.

Retail Unchained

When you consider the problems outlined above, you’re probably thinking, “there has to be a better way.” Maybe we can solve it with software? After all, “software eats the world,” right?

You’re not alone in your thinking. Many have had the same idea and an $8.9 billion business has developed around supply chain management. But, no matter how good the software, it can only go so far. You still have to move boxes around.

Remember the old GI Joe TV show? In it, at the end of every show, they would do a public service announcement and end it with, “…and knowing is half the battle.” Here’s my PSA:

Historically, it has been proven time-and-time-again that it’s better to push bits than atoms.