“We cannot enter into alliances until we are acquainted with the designs of our neighbors.”

― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

I’ve worked for Xerox Corporation twice in my career. The first time, from 1990 to 1994, happened to coincide with the launch of the Xerox DocuTech, which was a fire starter, arguably launching the era of digital printing. The demand was intense, but no where more so than in commercial print. Copy shops, quick printers, and others quickly realized the competitive advantage of a digital workflow. It was one of the few times in my career where selling was “easy.”

Then I worked for two large commercial printing companies who bought the same Xerox equipment I previously sold. The view is very different from the other side of the desk. These guys were selling clicks – not machines.

In the early days of digital printing, we all assumed that customers would use our services until they could justify their own equipment. Then we hoped they would retain us for overflow and for capabilities they didn’t have in house.

Wikipedia defines a killer application as “any computer program that is so necessary or desirable that it proves the core value of some larger technology.” But that definition is myopic. The term had meaning way before its use in software development. Healthcare benefits booklets and provider directories were a killer application for digital printing and a great example of the early symbiotic relationship between equipment manufacturers and service bureaus.

Once healthcare companies understood the value of digital printing – personalization, just in time manufacturing, etc., they began using it in earnest. That created short-term demand for service providers, and longer term demand for the equipment folk. Internal, “in-plant” print shops were still considered a good business practice, and healthcare companies started acquiring fleets of high-volume printers to support the growing demand.

But printers benefited too. At its peak, one healthcare company I worked with was outsourcing 20 million pages per month. That was the “overflow” on what was probably 60 million in total. Skids and skids of paper. Both the equipment providers and printers received their share. All was right with the world.

The idea behind facilities management makes sense. Some customers don’t want to buy equipment, they just want the benefit. So instead, they lease. But, they still have all kinds of other expenses they’d like to get off the books. So, equipment manufacturers sold them on services. They’d install the equipment and run it, among other things. Sometimes they’d even move the shop off site.

At some point, greed set in. Someone said, “if we’re going to run print shops, we might as well run them at full capacity. Let’s hire some reps.”

Someone else probably said, “If we’re going to operate them off site, we might as well put them in retail spaces where we can draw traffic.”

By 1987, Xerox had nearly 60 Xerox Reproduction Centers scattered across the country. They were retail print shops, owned by Xerox.

They were also a thorn in the side of anyone selling Xerox equipment to commercial printers.

Imagine the scenario. I’d walk into a big account and the owner would say, “John, guess who I just lost so-and-so’s business to? You!” I’d go through my story about how we were all compartmentalized and if he was losing business, so was I.

The practice became known as supplier competition. The print-for-pay industry highly resented manufacturers who played in their space. Why not? Theoretically at least, manufacturers were using their own equipment, their own supplies, and their own paper. That was all stuff they sold at a profit to their print-for-pay customers. They could simply use that margin to undercut their customer.

Supplier competition is talked about less today. With consolidation, the remaining large printers can compete more effectively. RR Donnelley for instance, is now so large that there are occasions where its plants actually compete against each other.

Over time Xerox closed its reproduction centers and mainstreamed their facilities management business. Advancements in technology have also changed the game. Even the term “facilities management” has evolved. Managed Print Services (MPS) are the new thing.

But, how does this apply to 3D printing?

Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it.

Over the past 10 years, 3D Systems purchased several service bureaus and now sells output from multiple facilities. Stratasys had its own production center (RedEye), bought two very large service bureaus (Solid Concepts and Harvest Technologies) and merged them to form Stratasys Direct Manufacturing.

They’re not alone.

Many 3D printing equipment dealerships also offer production outsourcing. In fact, at least one office equipment dealer I know has delayed his entry into 3D printing, specifically because he wants to decide on which side of the fence he’ll sit. He’s been through the supplier competition ringer before and this time intends to act strategically.

Even a newcomer has made clear its intent to play both sides. A while back, Ricoh announced it would enter the 3D printing market, stating in its press release that it would, “…sell 3D printers and its associated output service directly to manufacturing customers, as well as provide consulting services to these customers using first-hand knowledge and experience.”

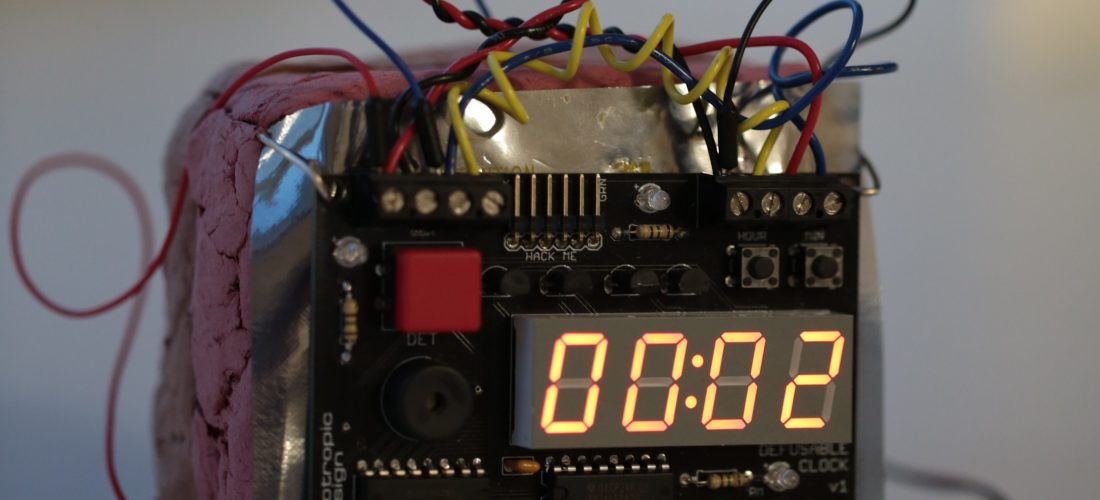

SUPPLIER COMPETITION IS 3D PRINTING’S TICKING TIMEBOMB

The industry can’t possibly think this will work, right?

As demand for 3D printing grows, the print-for-pay segment is certain to explode. For-pay makerspaces and 3D print shops will proliferate. More and more independent service bureaus will come online. In addition, retailers and others will bring 3D printers in-store. The UPS Store and Staples are already doing it. The manufacturers will happily sell them gear. Their print-for-pay customers will hire salespeople and conduct marketing campaigns. They’ll eventually go to close a deal, only to find out their competition is also their vendor.

3D printing equipment sales reps, get your knee pads ready. It’s going to get ugly. Maybe go with something like this, “Ms. Customer, at blah-blah-blah 3D printer company, we’re compartmentalized. I don’t communicate with their sales team. I only sell equipment to service bureaus like yours. When you lose, so do I. If you had our latest upgraded super 3D printer you could be more competitive. It’s 4% faster.” Make sure you wear your flak jacket to that meeting.

For new manufacturers entering the market this could be a big competitive advantage. Make the decision upfront. We’re either going to sell boxes or we’re going to sell output. If boxes, let’s help our print-for-pay customers generate revenue. Grow with them as partners.

How? Teach them how to sell your solution. Introduce them to prospective business. Market cooperatively. At Xerox I spent a lot of time working with my client’s sales teams. It was win-win. The more print they sold, the more boxes we sold. Later when I worked for a commercial printer, HP approached us about doing some cooperative marketing. They paid us, just like any other print job, to run and send direct mailers advertising our service. The business it generated lead to the placement of more HP equipment.

Fast forward to a few years from now when the technology has advanced to the point where multiple vendors all offer machines that are fast, produce good quality, and costs are somewhat commoditized. In those years, manufacturers will need to sell value – not speeds-and-feeds. Would you rather have to explain why you’re the competition, or instead spend your time discussing how you’ll help your customer build their business?

It’s not a scenario where we’ll have to wait to find out which model works. History provides a pretty clear map of where this is heading. The path towards disruption.