Additive manufacturing is decades old and yet the debate still rages on. Will it eventually replace mass production, or will the technologies cooperate? In a new tooling use case, Fortify and Henkel make an interesting argument for coexistence.

More Is Less

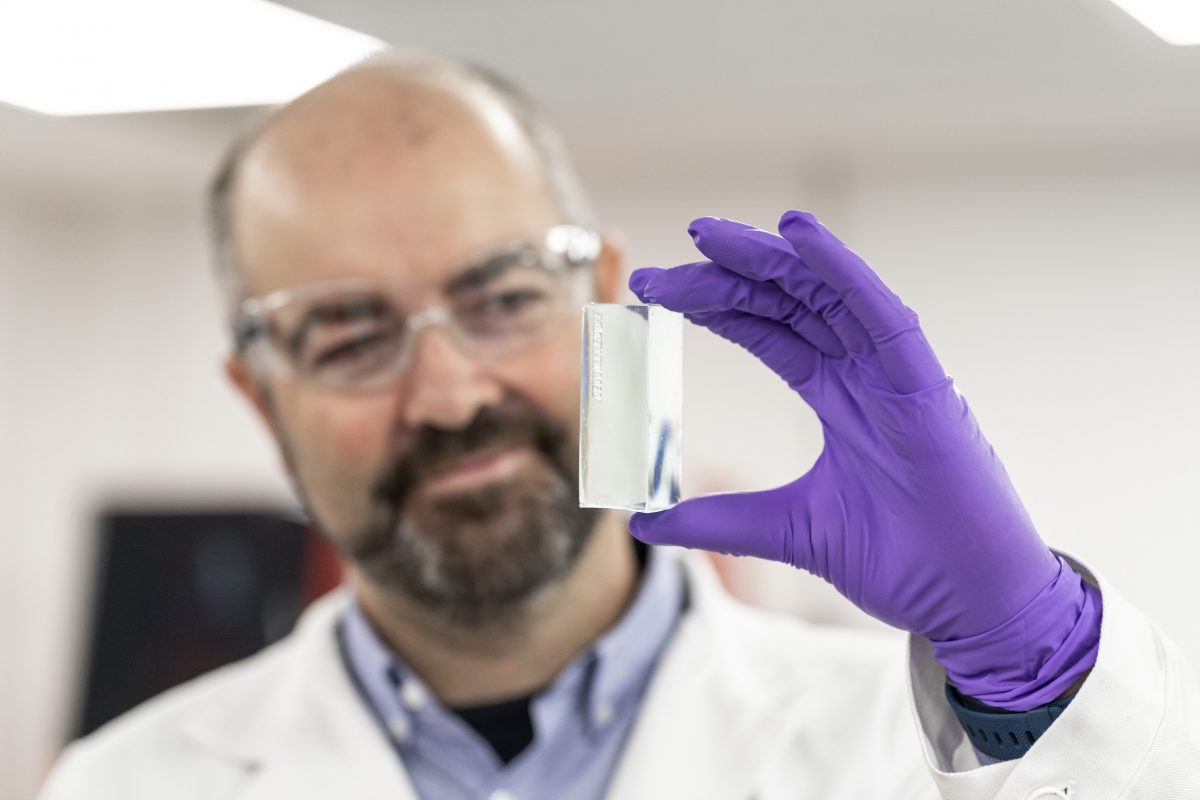

3D printed tool used to mold an automotive part (via Fortify)

When it comes to making plastic parts, injection molding is the de facto standard. The quality is outstanding, it’s fast and depending on your run quantity, relatively cheap. But that’s where the trouble starts. Injection molding operates off the same pricing principles as pretty much every other mass manufacturing technology. The more you make, the less you pay (per part.)

The biggest reason of course, is the cost of making a mold. It can easily cost $20,000 or more to make a mold for a simple plastic part. When you’re making 500,000 parts this is easily absorbed. When you’re making 25,000, not so much. If you’re in the prototyping stage, or need to run very low volumes the mold cost is typically prohibitive.

The knee-jerk response is to say, “well, that’s what additive manufacturing’s for.” But there are many reasons why you might still want to injection mold. You might want a unique material or want to over-mold the part. You could also be testing the process, knowing that once everything is set, you’ll be molding the final product.

3D Printed Molds Change the Game

Apparently it’s no longer an either/or scenario. Innovative companies like Fortify and Henkel are working together to help injection molders 3D print inserts for their molds. Doing it this way can drop the cost by thousands of dollars, making it more practical to mold prototypes and even produce low volumes.

“When prototyping or producing parts in small runs, tooling cost and time are major barriers,” Karlo Delos Reyes, Vice President of Applications and Co-Founder at Fortify said in a recent press release. “With our 3D printed molds that utilize Henkel’s resin, we have proved the viability of these tools for low production runs. As we help injection molders reduce the expense and time involved with producing molds, they can quickly react to new opportunities.”

While this application has been tried before, it’s not easily to accomplish. The inside temperatures of a mold can easily reach 300+ degrees F. The material used to make the insert must be strong, durable and heat resistant.

For its part Fortify supplies a unique 3D printing technology called Digital Composite Manufacturing (DCM) which uses magnetics to align composite fibers within the material being produced. In the case of mold applications, the fibers are ceramic. Henkel supplies the base material, which itself offers high strength and heat deflection. Together, this enables a product which can withstand the heat and pressure involved with injection molding.

At formnext 2019, the companies showed off mold inserts that were 3D printed. From Henkel’s perspective, it’s a clear example of leveraging their Open Materials Network strategy.

“We’re excited about the benefits Fortify’s technology can offer our industrial customers,” Ken Kisner, Innovation Lead for 3D printing at Henkel and founder of Molecule Corp., which was acquired by Henkel earlier this year, noted in the press release. “As new applications are unearthed, our development team is working quickly to help qualify and validate them. We have a wide range of materials in our portfolio and we’re committed to leveraging our knowledge and technology, in partnership with customers and companies like Fortify, to accelerate the growth of additive manufacturing.”

Working with Henkel, Fortify will begin beta testing in spring 2020. Beyond inserts for injection molding, they’re also looking at several end use part applications where their combined solutions deliver significant value.

From my perspective, it further demonstrates the cooperative nature of emerging technologies. It’s easy to think of a 3D printer sitting next to an injection molding machine. As soon as the image pops in my head, it comes with a flood of business rules. If the volume is less than X it gets 3D printed, if more it gets mass produced, etc. This application serves as a reminder that sometimes, the answer is far more complex.